By Julia DEC

Edited by Kristína SATKOVA

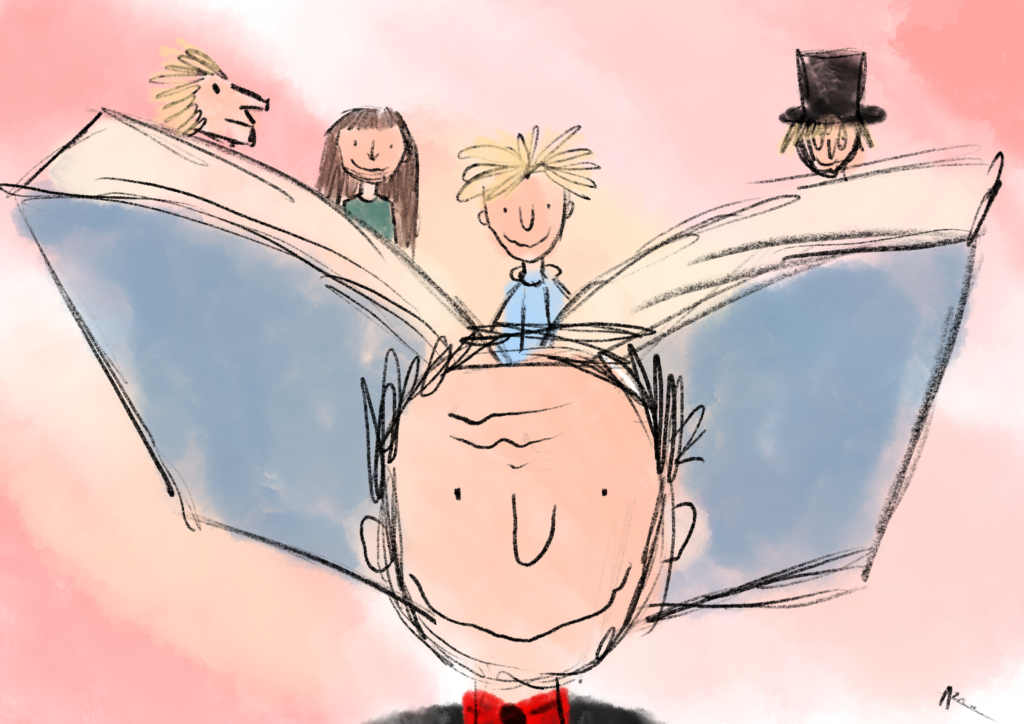

I first encountered Roald Dahl’s poetry and books as a gawky, literature-loving girl in primary school. Noted for his eccentric contributions to children’s literature, Dahl is most famous for his books “James and the Giant Peach”, “Matilda”, “The BFG”, “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” … the list goes on. I distinctly remember the ludicrous faces my class would make upon hearing the unfiltered gore of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” (the Queen ate what she presumed to be Snow White’s heart!), and the blotchy watercolour sketches of Quentin Blake, who vivified the perfect absurdity of Dahl’s stories.

For many, Roald Dahl’s prose had been the first medium of exposure to taboo topics. His unashamed bluntness gave the poet a groovy, dare-devil household name. As we all know, kids are innately curious – and Dahl’s works allowed young kooks to safely explore that inquisitive part of themselves, all the while granting his readers a good laugh. However, as a teenager who is once again peering into Roald Dahl’s whimsical world, I can’t help but hold a magnifying glass over the very mature and very real undertones of his work, which deviate away from my child’s tunnel vision. Is Roald Dahl really the jovial, lighthearted grandpa we grew up to love the works of, or is he also a multi-layered, political critic?

Pig (1960)

“In England once there lived a big

A wonderfully clever pig.

To everybody it was plain

That Piggy had a massive brain.

[…]

He knew all this, but in the end

One question drove him round the bend:

He simply couldn’t puzzle out

What LIFE was really all about.

[…]

Till suddenly one wondrous night.

All in a flash he saw the light.

He jumped up like a ballet dancer

And yelled, “By gum, I’ve got the answer!’

‘They want my bacon slice by slice

‘To sell at a tremendous price!’

[…]

‘The butcher’s shop! The carving knife!

‘That is the reason for my life!’”

Masked by the couplets’ unified nursery-style rhyme, the poem forces us to step into the pig’s shoes – not only are we magically granted a straightforward meaning to life – we are made aware that despite our intellect, our fate is to be discarded by the sloppy and bloody means of literal consumption. Concluding the poem gruesomely, the swine reverses the consumer-consumed dynamic, and instead eats the farmer who is introduced later in the poem, “Next morning, in comes Farmer Bland / A pail of pigswill in his hand / And piggy with a mighty roar, / Bashes the farmer to the floor…”. What follows is a horribly tangible procession of Pig devouring Bland.

One of the poem’s primary moral takeaways is the concept of fate – and hence the manipulation of it. Despite Pig’s enriched noggin, the farmer still considers him as disposably edible, and Piggy turned the tables – through which Dahl narrates the idea of taking destiny into one’s own hands. On a more theoretical note, one can’t miss the underlying theme of criticism towards capitalist economy – after all, to older readers, the comparison of pigs to men is reminiscent of Orwell’s “Animal Farm”. A new layer of the story is introduced – the theme of greed-corded morality and possibly an “eat the rich” undertone.

Like with many things in life, new perspectives are gained growing up. When exploring the metamorphosis of opinion with age, your teenage or adult version is much more prone to deconstructing a piece of media for something more than sweet nostalgia, color, and superficiality. In Dahl’s case, it is not surprising that his poems and books bear that polysemy which transforms his words into striking evergreens enjoyed by all ages, by all people. And to simplify it all – this multilayered storytelling is what makes Dahl’s work so powerful.

*Note: Writing this article, I acknowledge that I did not touch on Dahl’s controversies surrounding anti-Semitism and other problematic views expressed in his writing and personal statements. Certain readers consider Dahl’s views on various social issues, including gender and race, offensive or outdated. In recent years, publishers have made efforts to edit some of his texts to remove language deemed offensive, which has sparked further debate about censorship in literature and the balance between preserving an author’s original work and making it more inclusive for modern audiences.